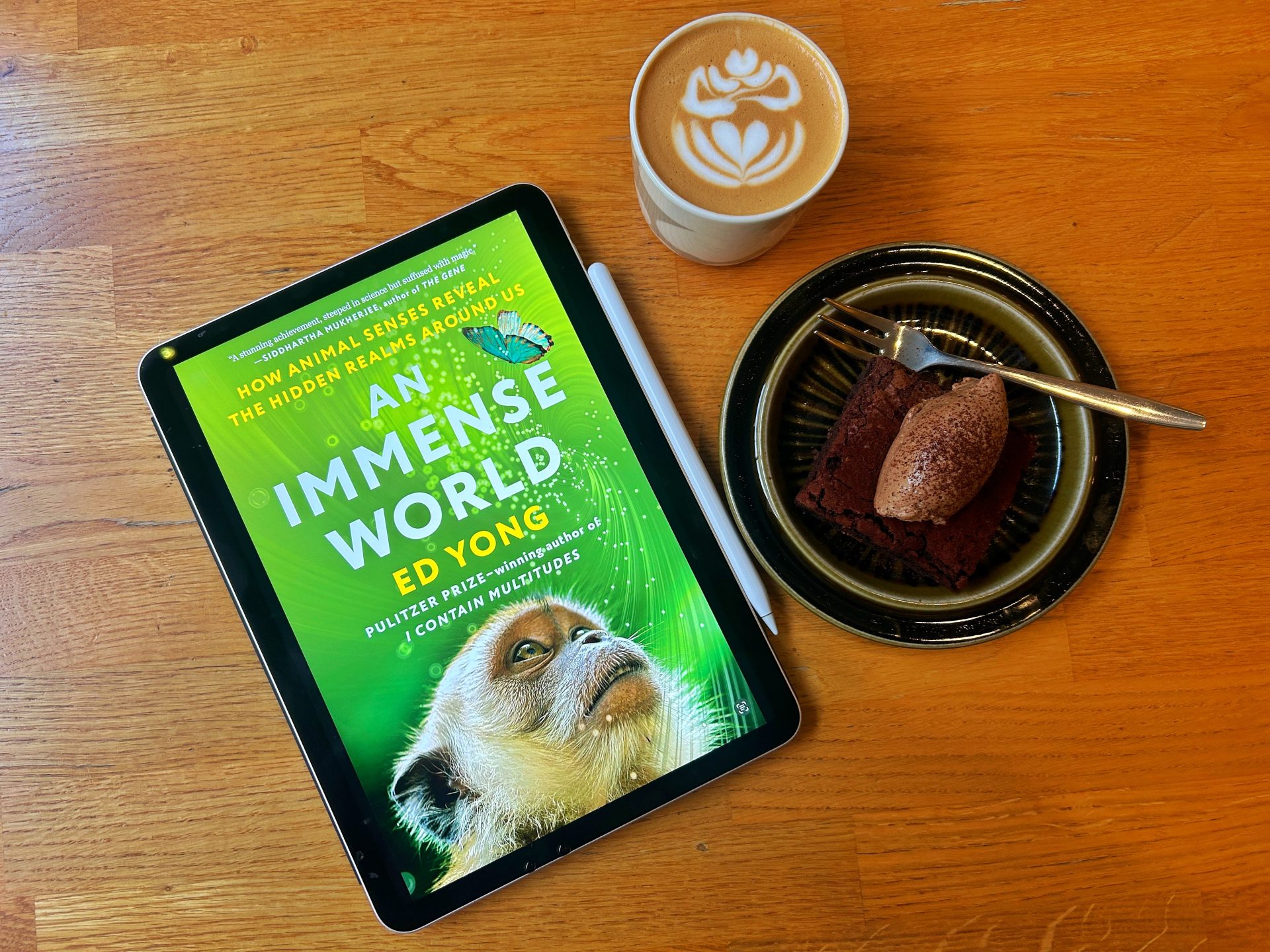

When we think about animals, it’s easy to get caught up in comparisons: how they measure up to us or how we can use them to advance our own knowledge. But An Immense World by Ed Yong shifts the narrative. This book celebrates diversity by seeing animals as they are, on their own terms, through their unique sensory experiences.

Yong introduces us through an uncommon term calls the umwelten, the sensory worlds of animals. Some scientists use these creatures to understand more about ourselves. For instance, electric fish, bats, and owls help us study our own senses, while other researchers reverse-engineer animal abilities to create new technology. Lobster eyes have inspired space telescopes, the ears of a parasitic fly have influenced hearing aids, and dolphin sonar has helped refine military sonar systems. It’s mind-blowing to see how much we’ve learned from nature’s ingenuity.

Yong explains how each animal’s senses define its life: what it can perceive and how it interacts with the world. These senses even shape a species’ future and its evolutionary path. Yong challenges us to go beyond anthropomorphism, which is the tendency to project human emotions and traits onto animals. Instead, he invites us to step into their shoes (or paws or fins) and imagine the world through their senses.

This idea resonated deeply with me. I live near an arboretum, and winters in Finland are long and dark. By 3 or 4 p.m., it’s already pitch black, and even by 9 a.m., the sun is slow to rise. Many people use the forest path in the arboretum as a shortcut from the city center, and the darkness around my home often makes it challenging for me to come and go. While I sometimes wish the city would install streetlights for safety, I’m also mindful of how artificial lighting disrupts the animals nearby. I’ve often seen hares and fawns darting around my home, and based on the information board at the arboretum, I know there are many more animals I don’t see. It’s a constant reminder that our needs, like streetlights for convenience, can conflict with the natural rhythms of wildlife. I truly appreciate the city’s decision not to install lights, respecting the animals’ space and ensuring they aren’t driven away.

Yong’s writing brought that kind of issues into sharper focus, highlighting how seemingly small human conveniences can create big problems for animals. Coastal lights disorient sea turtles, underwater noise drowns out whale songs, and glass panes confuse bats into thinking they’re flying over water. What feels harmless to us can cause significant harm to them.

One of the most profound lessons from this book is that every creature is shaped by the house of its senses. Our own experience of the world is just one version of what’s out there. There’s so much richness we miss simply because our senses filter it out. Yong’s words are a gentle reminder that there’s light in darkness, sound in silence, and so much more to discover in what seems like nothingness.

The book also emphasizes how paying attention to animals deepens our understanding of the world. When we learn to see life from their perspective, our own lives become richer. And if you’re worried you might get lost in some of the complex descriptions of animal features, don’t be! The book includes illustrations at the end, making it easier to visualize what Yong describes. Of course, seeing these animals in real life would be even more magical, but the book ensures you won’t feel left out.

An Immense World invites us to expand our view of life on Earth. By understanding and respecting the diverse sensory worlds of animals, we gain a deeper appreciation for the interconnectedness of all living things.

Summary

How Our Vision Shapes Our Understanding of Animals

When we think about animals, our perspective is heavily influenced by our own senses, especially vision. Humans rely so much on sight that even those who have been blind since birth often use visual terms and metaphors to describe the world. This deeply ingrained bias colors how we perceive and understand other species.

Understanding the Umwelt, An Animal’s Unique Perceptual World

The term umwelt, introduced in 1909 by Baltic-German zoologist Jakob von Uexküll, captures the idea of an animal’s unique sensory world. Uexküll likened an animal’s body to a house with windows opening onto a garden. Each “window” represents a different sense—sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. The way these windows are “built” determines how the garden, or the world, is perceived. Importantly, this garden isn’t a fragment of a universal reality but the only world the inhabitant knows—its umwelt.

An animal’s umwelt refers specifically to the part of its surroundings it can sense and experience. For example, a tick’s world revolves around detecting body heat, the feel of hair, and the smell of butyric acid emitted by mammalian skin. These three cues define its entire perceptual universe, demonstrating how drastically different an umwelt can be from our own.

The Unique Power of Smell

Unlike light, which travels in straight lines and fades quickly, smells have a more dynamic and enduring presence. They diffuse, seep, swirl, and flood, moving effortlessly through darkness and around corners—places where vision struggles. Smells linger in the air long after their source is gone, acting as a sensory time machine that reveals traces of the past in a way light never could.

Ant Communication

For ants, communication revolves entirely around chemistry. These blind, underground-dwelling creatures “antennate” one another—essentially their version of sniffing. By tapping and inspecting the chemicals on each other’s bodies, ants identify colony-mates and detect intruders. The key to their chemical language lies in pheromones, which are signals shared exclusively within the same species and have consistent meanings across individuals.

Ants use a variety of pheromones for different purposes, leveraging their unique chemical properties:

- Lightweight pheromones: These rise quickly into the air, serving as rapid-response signals. For example, when an ant’s head is crushed, aerosolized pheromones instantly alert nearby colony-mates to attack. These volatile chemicals can summon large groups to overwhelm prey or respond to danger.

- Medium-weight pheromones: Slower to disperse, these chemicals are ideal for marking foraging trails. When an ant finds food, it lays down a chemical path that others can follow. The more ants travel the path, the stronger the trail becomes. Once the food supply dwindles, the trail naturally fades.

- Heavyweight pheromones: These scarcely aerosolize and remain on the ants’ bodies as cuticular hydrocarbons. Acting like identity badges, these chemicals help ants distinguish species, colony-mates, and even roles like queen versus worker. Queens use these substances strategically, such as preventing workers from breeding or marking disobedient ants for discipline.

This intricate use of pheromones underscores the complexity of ant societies and their reliance on a highly evolved chemical communication system.

Catfish, the Masters of Taste

Catfish possess the most advanced sense of taste in the animal kingdom, with taste buds covering their entire scale-free bodies. This unique adaptation allows them to detect flavors through their skin, making them exquisitely sensitive to amino acids—essential nutrients found in their aquatic environment. However, catfish are notably poor at detecting sugars, a trait shared by many other specialized animals.

For instance, vampire bats, which exclusively consume blood, have lost the ability to taste sweetness or umami. Similarly, pandas, with their bamboo-based diet, no longer sense umami but have evolved extra bitter-sensing genes. These help them avoid the toxins lurking in the many varieties of bamboo they consume. This variation in taste sensitivity reveals how an animal’s diet shapes its sensory world.

The Marvel of Colors, Beyond Our Limited Perception

Whether we see the world as a monochromat, dichromat, trichromat, or tetrachromat, we tend to take the colors we perceive for granted. Each of us is confined to our own umwelt—our unique sensory bubble. The true wonder of colors lies not in how many hues one individual can see but in the incredible diversity of rainbows that exist across different perspectives. This range highlights the richness of sensory experiences beyond our own.

The Complexity of Pain

Pain is deeply subjective and varies widely across species. Just as light wavelengths aren’t inherently “red” or “blue,” and odors aren’t universally “pleasant” or “pungent,” nothing is universally painful. Each species has evolved to navigate its environment, tolerating some discomforts while avoiding others, making it incredibly difficult to determine what might cause an animal pain.

Take squid, for example. When injured, they behave as though their entire body is sore, becoming hypersensitive. This heightened alertness might seem excessive, but it serves a purpose: injured squid are particularly vulnerable to predators, as they become more noticeable and seem easier to catch. By setting their entire body on high alert, squid may increase their chances of escaping attacks from any direction.

Octopuses, in contrast, display remarkable dexterity in caring for themselves. They can reach inside their bodies to groom their gills—akin to a human scratching their lungs. Injured octopuses often retreat to solitary dens to recover, tending to their wounds with precision. If an arm tip is injured, they may break it off entirely. The resulting stump becomes highly sensitive, and octopuses have been observed cradling it gently in their beaks.

These differences highlight how each species has evolved its own relationship with pain, shaped by survival needs and physical capabilities.

How Understanding the Senses Can Help Save the Natural World

A deeper understanding of sensory worlds offers insights into how we’re damaging nature and how we might save it. In 2016, marine biologist Tim Gordon witnessed the devastating effects of a heatwave on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. The extreme temperatures caused corals to expel the symbiotic algae that provide them with nutrients and vibrant colors. Starving and bleaching, the corals weren’t just visually lifeless—they had also gone silent.

The usual sounds of snapping shrimps and crunching parrotfish, which guide baby fish back to the reef after their vulnerable early months at sea, were gone. The result? Silent reefs were uninviting to young fish, allowing seaweed to overrun the coral, preventing recovery.

To address this, Gordon and his team set up loudspeakers on patches of coral rubble, playing recordings from healthy reefs. The results were astonishing: reefs enriched with these sounds attracted twice as many young fish and 50% more species than silent areas. These fish didn’t just visit—they stayed and started forming communities.

While promising, this is only a small-scale solution. Without tackling the root cause—climate change driven by carbon emissions—the future of coral reefs remains bleak. However, restoring the natural sounds of degraded reefs might give them a better chance of survival, making conservation efforts less overwhelming.

Gordon’s experiment also underscores the urgency of preserving the natural “soundscapes” that still exist. Instead of adding back stimuli we’ve removed, like coral sounds, we can often protect nature by simply eliminating the disruptions we’ve introduced—an easier fix than dealing with most pollutants.

Ultimately, while individual actions are valuable, they cannot make up for the societal inaction and irresponsibility that continue to fuel environmental crises.

The Silent Loss of Connection to Nature

As animals disappear from our lives, we grow accustomed to their absence. This detachment dulls our urgency to tackle sensory pollution, even as it continues to harm the natural world.

While we may never fully understand what it’s like to be an octopus or any other creature, we are fortunate to know they exist and that their experiences differ from ours. Through careful observation, advanced technologies, the scientific method, and most importantly, curiosity and imagination, we can attempt to step into their worlds.

This opportunity to explore and understand is a privilege, one we didn’t earn but must cherish. Choosing to connect with and protect the sensory landscapes of other beings isn’t just an act of curiosity, it’s a responsibility we must embrace.

Author: Ed Yong

Publication date: 21 June 2022

Number of pages: 464 pages

Leave a Reply